By Gail Copeland, granddaughter of Arthur Copeland – POW (prisoner of war) at Schweidnitz Camp from early December 1917 until April 1918.

POW officers constantly schemed and planned on how they could escape. Many felt it was their duty to try. Perhaps they needed to return to fighting in the war; maybe the conditions of confinement were intolerable, or they just wanted to return home to loved ones. According to Eric Fulton, one of the twenty-four men who made it out on the night of March 19, 1918, each camp set up an escape committee. If someone came up with an idea for an escape that seemed viable, the entire camp would start to collect whatever necessary equipment they could find. If there was an escape plan in progress, prisoners had to get permission, from the committee, to start another plan. This ensured that if one escape attempt was discovered and a camp search was undertaken, they would not inadvertently discover another scheme in the works.

If your ancestors were claustrophobic or perhaps carried a few extra pounds, then rest assured, they were unlikely to have chosen to escape through a twenty-inch diameter tunnel. The tunnel used in this escape was made just wide enough that a man could crawl on his belly, using his elbows and knees. To make it larger would mean a longer completion time and the likelihood of collapse was greater. My grandfather, Arthur Copeland, would have made a good candidate since he was about five feet, eight inches tall and weighed one hundred and twenty-five pounds. The flimsy aircraft in use in WWI could not carry a lot of weight, so the Royal Flying Corps tended to recruit men of smaller stature. It was not surprising that more than half the escapees were from the Flying Corps.

I think you’ll find it helpful to look at the map below. The locations of several structures mentioned in this article can be found. This map was drawn by Aubrey Rickards, complete with escape routes.

|

| Camp map by Rickards (permission given by James Offer) |

Prior to the successful tunnel, located under Barracks 4, there had been several others started and discarded. According to escapee, Aubrey Rickards, the first tunnel was started in the church, a second tunnel originated in the well, located in the middle of the exercise area, and a third tunnel was located under the floor of the kitchen.

To allow diggers access to the cellar of Barracks 4, two floorboards were pried up. The cellar was mostly used for potatoes, vegetables and some crated goods. After removing some bricks from the walls, they started to dig. Some of the dirt could be dispersed in the cellar and some was discarded outside. The hole was dug in shifts by one man at a time. Other men stood guard in case a sentry came by. The air in the tunnel was very bad, so the shifts were short. Great care had to be taken to limit contact with the sides of the tunnel. No one wanted a cave-in. When they emerged from the hole, covered in dirt, they had to be able to change quickly into clean clothing. Aubrey Rickards said their only tools were a screwdriver and a tin plate. After six weeks, it was felt that the tunnel was long enough, at twenty-four feet. Having gotten past the outer wall that surrounded the entire prison yard, it was time to tunnel upward. Their first attempt to reach the surface was unsuccessful, as they came to a concrete obstruction and had to dig a slight detour. It turned out that the blockage was the floor of the pigsty. On their second attempt to break through, they were successful. Of course the exit was in the middle of the pigsty!

|

| A Sketch of the Escape Route and the Infamous Pigpen (Courtesy James Offer) |

Although the actual digging was only conducted by a handful of officers, there were many more who had helped to disperse dirt from the tunnel, stood guard during tunnelling, and found materials needed for the escape. Forty-eight men hoped to escape on the night of March 19, 1918. Throughout the day, these men brought their kits over to Barracks 4. The kits consisted of rucksacks that held all the supplies they’d need once they were free. Studying the German language was a popular past time for prisoners. If you were planning on escaping and spoke passable German, you’d have far better luck than those who only spoke English.

Those men, who regularly slept in Barracks 4, but weren’t involved in the escape, traded places with the potential escapees. By the 8 p.m. roll call, all the escapees were under one roof. The working parties went out first. Unfortunately, only twenty-four of the forty-eight hopefuls, managed to escape, as the twenty-fifth man got stuck in the tunnel. It was decided that everyone would travel in groups of twos. As no shots were fired after the first party went through, the second group started out. This continued, at ten minute intervals, until early in the morning of the 20th. There were many delays as men would get stuck and have to be pushed and pulled from both ends.

The weather was cold at that time of year and there was still snow on the ground. It was a daunting challenge to set out for neutral frontiers, almost eight hundred kilometers away. Twenty-four men emerged from the tunnel and disappeared into the night. Some were captured the next day, while others lasted weeks. By March 28th, there were only two men still on the loose. Many were captured at train stations, others while walking in towns, or hiding in the forests. They dispersed in all directions. Some headed toward Switzerland, while others headed for Holland. Records indicate that several men made it close to two hundred kilometers before being captured. Just think about how hard that would have been to do, while travelling mostly at night. Sadly, by early April 1918, all had been recaptured. If only we had all their stories.

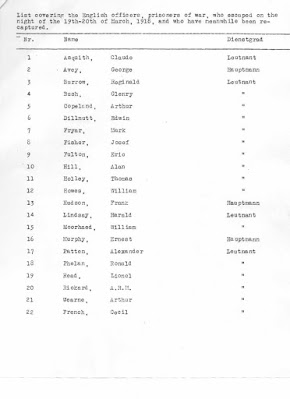

The list of escapees recaptured - Later recaptured are George Tarn Harker and George Atkins

If you have a relative included in this escape please contact us.