by Simonne Waud, Willie's granddaughter

|

| William Bradshaw Moorhead |

William Bradshaw Moorhead, known by family and friends as ‘Willie’, was born in north-east China on 11th December 1893. His parents were living in Chinkiang (now called Zhenjiang), a British concession city and natural inland river port on the southern bank of the famous Yangtze River about 175 miles upstream from the city of Shanghai. Willie was the eldest child of Irish born John Hercules Murray Moorhead and Lily (née Forbes) of Scots descent. Only five of their children lived beyond infancy.

Willie’s father was known as ‘Jack’ and he was stationed in China as an employee of the Chinese Customs Service. Originally from the north of Ireland, two generations of the Moorhead family were employed by the Chinese Imperial Maritime Customs Service, which was run on behalf of the Chinese by fellow Irishman and childhood friend Robert Hart, later Sir Robert Hart.

Willie’s mother, Lily, was eleven years younger than Jack. She was born in 1870 in the British Consulate in Tientsin, in northern China, to a Scottish merchant called William Forbes and his wife Martha (née Lockhart). Lily was diminutive in stature but had a personality to more than compensate - she liked to rule the roost! Jack and Lily were married in London in 1892.

Jack and Lily Moorhead returned to China and Willie was born the following year. His siblings followed at regular intervals - Amy Matilda Jane, known as Cissy (b.1895, Chefoo, China); John Robert (b. 1897, d. 1899 Chinkiang, China); Hercules Bradshaw Forbes, known as ‘Herrie’ (b. 1901, Cheltenham, England); Lily Forbes, known as ‘Pussy’ (b.1908, Folkestone, England); Eileen Bradshaw (b. 1912, Chinkiang, China) and her twin Robert Bradshaw (b.1912, d. 1912).

When the boys were considered old enough (probably aged about seven or eight, and very young by today’s standards) they were sent off to prep school in England while other members of their family returned to China. An English education for the children, particularly the boys, was considered a greater priority than family unity. After prep school Willie was educated at Marlborough College, a private boarding school for boys in Wiltshire.

The 1911 census shows Lily Moorhead, with her children Willie, Cissy, Herrie and Pussy, plus two household staff, living in England at a house in Edensor Road in the Meads area of Eastbourne in Sussex. Willie was 17 and still a student. His youngest siblings, a pair of twins, Eileen and Robert, were not yet born.

|

| Sandhurst Cadet uniform 1914 |

After school Willie attended the Royal Military College in Sandhurst as a Gentleman Cadet for officer training, probably for about 18 months. Upon graduation, on 15th August 1914, at the outbreak of World War I, Willie was commissioned, aged 20, as a 2nd Lieutenant into the highly regarded King's (Liverpool) Regiment, an infantry regiment of the British Regular Army, but he was not immediately sent to the war arena. It is quite possible that he was held in Regimental Reserve, and it may have been felt that he would benefit from additional training before being given a field command, and at that time, only two weeks into the war, the Regimental roster of officers was likely fully manned. The 1st Battalion of the King’s Regiment, which Willie eventually joined, disembarked in France on 13th August 1914, two days before his commissioning. Prior to Willie’s arrival in France, the Battalion fought in a number of significant battles, including the Battle of Mons (Belgium), the Battle of the Marne, the Battle of the Aisne and the first Battle of Ypres (Belgium).

Like all soldiers who travelled to Europe to fight in WWI, Willie witnessed unimaginable horrors in the trenches of the Somme, memories of which he never discussed openly. Willie saw active service with the 1st Battalion from 22nd November 1914 as a member of the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front in France and Belgium. He joined the Battalion at Caëstre in northern France shortly after it had played an active role in the First Battle of Ypres. The timing of his arrival at the beginning of the winter meant his first taste of life at the Front was characterized more by survival of the elements than facing the enemy in battle. The men were faced with constant rain, cold weather, mud, rats and vermin. One of the men from his Battalion died and disappeared five or six feet into the mud at the bottom of the trench. Part of the 1st Battalion participated in an assault against German positions on 10th March 1915 at Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée, about two km SE of Festubert, and suffered over 200 casualties, but it is not known whether Willie participated in this action. This would likely have been the earliest large action in which the 1st Battalion fought after Willie’s arrival.

Willie was promoted to Lieutenant on 27 April 1915. His first major battle appears to have been the Battle of Festubert, in which the Battalion most actively fought from 17th -19th May 1915. Although the attack was considered successful, the 1st Battalion suffered over 600 casualties (killed, missing or wounded), according to the battalion War Diary. The Battalion also participated in the even larger Battle of Loos in September 1915. This battle marked the first time in the war when the British used chlorine gas against the Germans.

On 18th January 1916 Willie was attached to 11 Squadron, the very first dedicated fighter and reconnaissance unit of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), at that time in its infancy and formed at Netheravon in Wiltshire. Willie was trained as a Lewis gun operator, an early machine gun used on a two-seater Vickers F.B. 5 ‘Gunbus” plane, and as the Observer he sat in front of the pilot manning a Lewis gun. The squadron was posted to northern France and on 7th February, Willie, along with a pilot named Lieutenant Geoffrey H. Norman, were sent on patrol. They were flying a Gunbus when “two cylinders blew off” the aircraft’s engine and they had to force land the plane east of the village of Allonville, near Amiens. Both men were unhurt and returned safely to their unit. In March that year Willie was appointed to the position of Observer on probationary status, but his stint with the RFC was short-lived – which was fortunate given that the average life expectancy of airmen at the time was just eight missions! His short stay with the RFC may have been intended as a means to give him more experience in the operation of the Lewis gun. After returning to his Battalion he was given the responsibility of being its Lewis Gun Officer.

|

| Vickers F.B. 5 ‘Gunbus” plane |

By the summer of 1916 Willie had returned to The 1st Battalion of The King’s Regiment. It is not known whether he was with the 1st Battalion during the month of June, most of which was spent manning the trenches at Vimy Ridge. Casualties were experienced, but there were no major battles during this period. Willie was likely back with the Battalion in time for its participation in the first Battle of the Somme at the beginning of July. The Battalion fought in Battle of Delville Wood, located about 3 km NNW of the small village of Guillemont, a German stronghold in the Somme Valley, in Northern France. Conditions were dire, with soldiers living and dying in the trenches, but in spite of these terrible conditions the British Army somehow retained a sense of humour. An old field map shows how they named the local roads after some well-known streets in London - Brompton Road, High Holborn, Fleet Street, Haymarket, Pall Mall, Cheapside, Rotton Row, etc.

On 8th August Willie’s Battalion was engaged in a battle with the Germans to capture Guillemont Station, on the NW edge of the village of Guillemont. This was part of a significant effort that day, by several British battalions, to once again attempt to capture the village and surrounding areas. The attack was unsuccessful. It was a brutal combat which resulted in heavy losses. From the 1st Battalion alone there were approx. 250 casualties (killed, wounded or missing) that day, including 15 officers and 235 other ranks.

During the fracas on the 8th August Willie’s Company became isolated and he was put out of action by a sniper hiding up a tree, who shot him in his upper left arm. Efforts to rescue the surrounded men were unsuccessful, despite intense artillery bombardment and attempts by other Battalions to break through to them. Captain Ernest Murphy and 2nd Lieutenant Reginald Burrow, two officers of the 8th (Irish) Battalion of The King’s (Liverpool) Regiment, were among the other officers taken prisoner that day not far from where Willie was captured. They were to spend the rest of their captivity with Willie Moorhead at various prisoner of war camps.

Willie was singled out by his Brigadier General following the battle as one of several “valuable officers” of the Battalion who were missing. His name appeared on the Casualty List issued by the War Office on 17th August, but not until 28th October did word get home that he was alive, wounded and captured. He was sent to St. Quentin for treatment by German medics in an enemy field hospital about 40 km south-east of Guillemont. Here they administered to some 350 wounded soldiers. Willie was then transported by train, with other British captives to a prisoner-of-war (POW) camp deep behind the German border.

The POWs were sent to the north-east of Germany and interned in early October 1916 at Hann Münden Officer’s Camp in Lower Saxony. Here Willie and his comrades endured the long cold winter months. Living conditions in officers’ camps were grim, but much less harsh than those endured by the lower ranks in other camps. Conditions in the POW camps were described in a previous blog.

Willie and a group of 166 army, navy and

flying officers, including eight of the future Schweidnitz tunnellers, were moved from

various camps to Augustabad at Neubrandenburg in early April 1917.

This POW camp was set in a former hotel

on the edge of the Tollensee Lake. The

camp was situated on the slope just above the lake enclosed by a wall and

25-foot high ramparts, with guards on constant watch. Fishing and bathing were permitted, but life

was no holiday and they endured endless periods of monotony, boredom and

intense frustration with their captivity.

POWs were moved around from one camp to another and by the end of the war there were over 70 officers’ camps scattered around Germany. After eight months at Augustabad 72 prisoners, including Willie and nine other future tunnellers, were transported to Schweidnitz (now within Poland and known as Świdnica) in Silesia in the east of Germany, near the old Polish and Czech borders. They arrived around the middle of December 1917. A description of the camp and life at Schweidnitz can be found in previous blogs on this site.

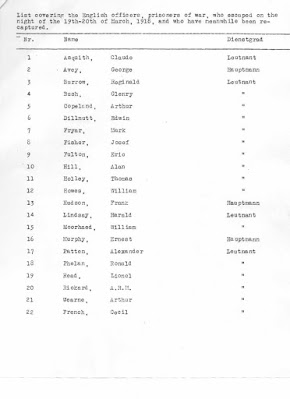

In March 1918 Willie and 23 other officers attempted to escape from Schweidnitz through a tunnel. Most of the 24 escapees travelled in pairs. We don’t know Willie’s escape partner, but his regimental colleagues Capt. Ernest Murphy and Lieutenant Reginald Burrow were two of those who broke free and it is possible one of them may have been his escape buddy.

Willie was recaptured and sent back to Schweidnitz briefly before being transported by train with the rest of the recaptured tunnellers to the large officers’ camp at Holzminden, arriving there on 16th April. The camp, nicknamed ‘Hellminden’, had a notorious reputation, as did its Commandant, Karl Niemeyer, a German national who had lived in the Midwest of America for 17 years. It was in Lower Saxony, in north-west Germany, and occupied a former cavalry barracks. In addition to several hundred officers, the camp, like many others, also held a number of “other ranks”, who acted as orderlies for the officers. It was a high security prison which was opened in September 1917 for British POWs, and many of the men sent there had been involved in earlier escape plots.

In June 1918, having spent almost two years in captivity, Willie was identified as eligible to transfer to a camp in neutral Holland as part of an English/German officer exchange. However, his transfer was delayed by the German authorities until October. Fellow Schweidnitz escapees, Asquith, Burrow, Bush, Fryar, Murphy and Patten were also transferred to Holland before the end of the war.

Planning for the largest and most celebrated escape of WWI was already well underway prior to the arrival of Willie and his cohorts at Holzminden. The tunnel escape took place on the night of 23rd/24th July, 1918. Some of the Schweidnitz tunnellers were known to have assisted behind the scenes with the Holzminden escape. The story has been told by several different authors, including Hugh Durnford, Neil Hanson, Neal Bascomb and Jacqueline Cook. In addition to the escape, these books also describe conditions at the camp and the oppressive regime of Commandant Niemeyer.

Meanwhile Willie remained at Holzminden awaiting trial by a German court for his break out from Schweidnitz. He lived through the Spanish ‘flu epidemic which swept across Europe for twenty-six months, including Holzminden, infecting over 90% of the prisoners during the months of July and August. Many people in the town died, but in the camp somehow the prisoners survived - probably due to the Red Cross supplies and parcels from home which offered a better diet to prisoners than the townspeople received.

On 27th September 1918, six months after their break for freedom from Schweidnitz, Willie and 18 fellow officers were tried by a German court martial at the Holzminden camp. They were sentenced to a further six months imprisonment with solitary confinement. The sentences were exceptionally harsh, but as the war ended shortly after they were never carried through. Despite this sentence, and perhaps as a result of remonstrations from British authorities in London on the grounds that his continued incarceration in Germany was in breach of the Hague Convention, German authorities finally allowed his exchange to Holland.

On 12th October 1918 Willie was transferred to an internment camp in Holland. The arrangement sent English and German officers to Holland, but they were not permitted to return to service. Though still technically incarcerated, ex-POWs at the Dutch camp enjoyed considerably improved freedom and living conditions. The two fellow Schweidnitz escapees, whom Willie was incarcerated ever since his capture in Guillemont, Burrow and Murphy, both arrived in Holland the same day as Willie, coming from Holzminden via Stralsund POW Camp.

After more than four long years the war finally came to an end on 11th November 1918, and Willie was quickly repatriated to England, arriving at Riverside Quay in Hull on the S.S. Porto on 22nd November. Following the Armistice Germany was very unstable due to protests, riots, and paralyzed transportation systems. He was lucky to get home relatively quickly, since most of his fellow prisoners didn’t arrive home until late in December.

Willie was awarded campaign medals including the 1914-15 Star, British War Medal (B.W.M) and The Victory Medal (V.M) for his active service. Aged almost 25, he had spent 27 months in captivity, something that caused him great anxiety and frustration. After the war he remained in the British Army and was promoted to Captain on 25th March 1920.

|

| "Willie" after WWI |

The King’s (Liverpool) Regiment, was posted to

Khartoum, Sudan in the early 1920’s and during this time Willie met his future

wife, Zillah Ellise Maloney. A nurse

since 1917, she was working with the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military

Nursing Service (QAIMNS) in Cairo, Egypt.

Willie returned from Egypt in August 1921. Zillah was demobbed as a Staff Nurse on in

May 1922.

Willie and Zillah were married on 18th August 1923 at St Mary’s Church in Gillingham, and their honeymoon was spent in Devon and Cornwall. Willie remained with The King’s Regiment while Zillah bore two children. Their son, Lindsey Murray Moorhead followed his father’s military footsteps, becoming an officer in the Grenadier Guards Regiment.

|

| St Mary's Church Gillingham |

Willie was promoted to Major in the King’s Regiment (Liverpool) in 1933, and was then stationed in India at Multan, followed by Peshawar, at the North West Frontier – now known as Pakistan. Willie and Zillah returned to England on leave after four years and then went back to India for another tour of duty. The family often spent time in Kashmir in the summer months to escape the heat.

In July 1940, at the beginning of WWII, Willie was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel of the King’s Regiment (Liverpool), but whilst still in India, he was diagnosed with cancer. He underwent successful treatment but was forced to return to England. Following his recovery, Willie was sent on light army duties to Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean. Having spent more than half of WWI incarcerated, and despite having experienced almost two years in the trenches of France, he was still very frustrated to find himself again kept out of frontline action, and away from his army comrades who were engaged in the action.

Willie returned home from the West Indies and was stationed at Tidworth in south-east Wiltshire on the eastern edge of Salisbury Plain. After Tidworth Willie retired from the King’s Liverpool Regiment on 7th March 1944 and the family moved to the village of Crowthorne, Berkshire, where they lived in a large ground floor flat in a large house called ‘Edgecumbe’.

Zillah died on 13th August 1959, aged 64, and was buried in a single grave at St. Peter’s Church, Frimley near Camberley in Surrey. Within less than a year Willie remarried and moved to Godalming. He was a keen gardener and spent much time pottering in the garden.

Willie’s mother Lily and sisters all had strong personalities, and Willie was the quiet one of the family. As an adult he was of smallish stature with blue eyes, brown hair and a neat moustache. He was an unassuming man, though prone to the occasional bouts of grumpiness with his grandchildren at the lunch table. He spoke very little about his life experiences and achievements. He liked routine and order; and he often left little instruction notes around the house, such as “Do not touch” or, on the central heating boiler, the message was something akin to “Do not meddle with this contraption!”.

Willie died on 28th May 1970, aged 76. He came in from the large garden, having mown the grass, and had a major stroke from which he never recovered. He was buried on 2nd June in the Moorhead family grave at St Peter’s Church, Frimley near Camberley.

o-O-o